Places of historicism

Wiesbaden is a city of the 19th century. This unique development is based on the fact that today's Hessian state capital grew from a modest small town with 2,500 inhabitants in 1800 to a large city with 100,000 inhabitants in 1905.

The unusual growth in the 19th century was associated with a storm of building activity. It is thanks to the astonishing change in form and the variety of styles of historicism that this development did not result in monotonous mass construction, which can quickly be the consequence when living space is needed quickly.

Wiesbaden has of course evolved over the last 100 years and today the city also displays the architectural design language of the 20th century. Nevertheless, as the city was lucky to have survived the Second World War with relatively little damage, it now presents itself as the most important "urban monument of historicism in Germany" (Professor Gottfried Kiesow).

This has prompted the city council and the magistrate to apply to have it inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

With a "Year of Historicism" in 2007, numerous events were held to draw attention to the architectural significance of the city. This year, the city applied for inclusion in the Unesco World Heritage List.

Places of historicism

As part of the application for inclusion in the Unesco World Heritage List, an overview of the places in the city that are emblematic of historicism was created. These can be individual buildings as well as entire streets. The project "On the spot - 100 places of historicism in Wiesbaden that you should know" focuses on the cityscape and its buildings. The Stadtmuseum project office was in charge of the project. The places are presented in pictures and words.

Villas

Beethovenstrasse 10

The villa at Beethovenstraße 10 is designed in neoclassical style, combined with elements of Art Nouveau.

The architect Paul Dietzsch from Essen designed the villa according to the representative needs of the client Heinrich Kirchhoff.

Bierstadt street 14

The building at Bierstadt Straße 14 is a castle-like villa built by architect Alfred Schellenberg in 1876-78 in the strict historicist style. The main façade faces west towards Rosenstraße. Schellenberg turned away from the usual symmetry of Classicism and Romantic Historicism and instead offset the villa's loggia to the south. His design was discreetly inspired by the Italian High Renaissance.

Villa Bierstadtter Straße 14 has been home to the private school Dr. Obermayr since 1975; only a few rooms still have their original furnishings.

The villa was demolished in 2024.

Bierstadt Street 15

In 1909, the architect Karl Köhler built the villa at 15 Bierstadt Straße for his own purposes in the neoclassical style, which was often reflected in the buildings of the First World War. Contrary to the actual custom of classicism, Köhler emphasized the roof of the villa by creating a mansard roof.

The building is the headquarters of the private school Dr. Obermayr.

Beautiful view 7

In the summer of 1883, Brahms worked on his "Wiesbaden Symphony", the 3rd Symphony in F major (op. 90), in a Wiesbaden villa at what was then Geisbergstraße 19.

Brahms' stay in Wiesbaden came about through his friendship with the Beckerath family, who initially invited him to their vineyard in Rüdesheim. After hiking together in the Swiss Alps and years of correspondence, Brahms finally returned to the Rheingau in 1883. Laura von Beckenrath found accommodation for the composer at Geisbergstraße 19 (today Schöne Aussicht 7). Brahms was able to compose there undisturbed in absolute peace and quiet, with walks from the front door. On his walks on the Neroberg and in the Taunus, his compositions unfolded almost to perfection; he then put the works on paper almost without corrections.

Brahms' work from his time in Wiesbaden was premiered on December 2, 1883 in Vienna with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra under Hans Richter.

Dambachtal 20

The villa at Dambachtal 20 was the home of Friedrich Werz, who - as can be seen from the building - appreciated the Art Nouveau style. He built the villa in 1905.

Gustav-Freytag-Straße 27

When Prince Albrecht, the owner of the Solmsschlösschen, fell seriously and apparently terminally ill shortly after moving in, he moved to Gustav-Freytag-Straße 27 in 1898 - the second villa he had built. In contrast to the monumental Solmsschlösschen, Prince Albrecht had the second villa built by the architect Wilhelm Köster in a relatively simple and conservative style. The villa is designed in the forms of the Upper Italian Renaissance, with an asymmetrical arrangement of the corner balconies.

Gustav-Freytag-Straße was called "Hainer Weg" until 1886 and was renamed after Gustav Freytag on the occasion of his 70th birthday. The poet lived in the villa at Gustav-Freytag-Straße 18 from 1881 until his death.

Frankfurter Straße 2

In 1842, the architect Georg Moller built the neoclassical-style "Villa Rettberg" on behalf of the Nassau lieutenant and adjutant to the duke, Carl von Rettberg. The owner died in 1844 and was laid to rest in the "Old Cemetery".

Influenced by the Italian Renaissance in its architectural forms, little remains of the villa's former appearance today. The building was enlarged in 1870 and a storey was added at the turn of the century, and its historic façade was altered. After the end of the war, the villa was renovated because it had been badly damaged by bombs. In 1949, the state government used the two neighboring buildings and Villa Rettberg as an office building.

After the Hessian State Chancellery moved into the former "Hotel Rose" in 2004, work began a year later to renovate the Villa Rettberg, including the adjoining coach house, and convert it into the Haus der Kommunen with a new office building.

Lessingstrasse 5

Villa Lessingstraße 5 bears the signature of architect Christian Dähne, who built nine magnificent neo-Renaissance villas in Wiesbaden.

Dähne built the villa in 1898 from brick and sandstone with three floors and a striking polygonal corner tower. The architect himself lived in the building for 26 years.

Sonnenberg Street 26/28

In 1899, the architect Wilhelm Boue built the double villa at Sonnenberg Straße 26/28 in the neo-baroque style. The "Regina" hotel was housed in the building between 1905 and 1935.

Viktoriastrasse 19

The company Kreizner & Hatzmann was responsible for the construction of Viktoriastrasse 19 in 1871/72. Two years earlier, Friedrich Hatzmann and Joseph Kreizner bought the building plot, of which they kept only a third themselves. In 1872, the two building contractors sold the neoclassical building at Viktoriastrasse 13 (now 19), which was decorated with larger-than-life caryatids from Höppli's workshop. The building, designed as a detached house, was converted into a multi-storey house around 1936.

While the villa itself only suffered minor damage during the Second World War, the coach house and stable buildings at the rear of the property did not survive the bombing raids.

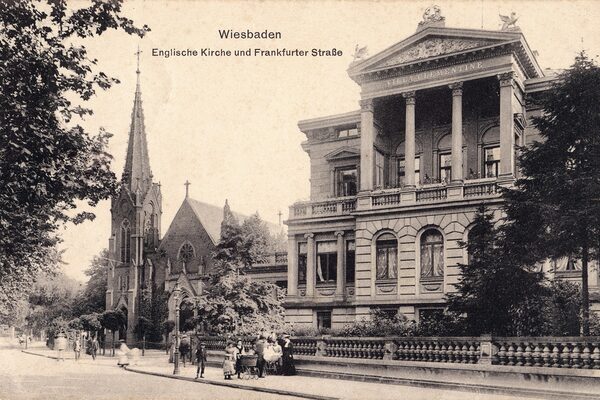

Frankfurter Straße 1 - Villa Clementine

Between 1878 and 1882, the architect Georg Friedrich Fürstchen built the Villa Clementine on behalf of the Mainz manufacturer Ernst Mayer. It was named after Mayer's wife Clementine, who died shortly after its completion. The architect, who was 29 years old at the time, designed the floor plan of the "upper middle-class villa" in a U-shape and finished the building with a double façade facing Wilhelmstrasse and Warme Damm. Fürstchen specified different heights for the rooms on the ground, first and second floors in order to emphasize the importance of the individual storeys. The building is also characterized by extraordinary stucco ceilings, several winter gardens and terraces as well as black marble steps in the stairwell.

Villa Clementine achieved worldwide fame in 1888 with the "Wiesbaden prince robbery": Serbian Queen Natalie rented the villa with her son, Crown Prince Alexander, after she had left her husband, King Milan Obrenovich. However, he tracked down her whereabouts and had his son brought back to Bucharest by order. Villa Clementine has been the home of the Wiesbaden House of Literature since 2001.

Biebricher Allee 42

Commissioned by the widow L. Wintermeyer, the architect Georg Schlink began building the villa on Biebricher Allee in 1902. The building stands out due to its corner location, the polygonal corner tower with baroque dome and the veranda, which was added on the Biebricher Allee side. In 1914, another veranda was added to the rear of the building. The current name "Villa Schnitzler" comes from the second owner.

Paulinenstrasse 7

The official residence of the President of the United States in Washington was unmistakably the model for the construction of the "White House" villa. This was at the request of the American wife of the champagne manufacturer Söhnlein, Emma Pabst. However, it is also possible that the emerging neoclassicism influenced the design of the house. The Swiss architects Otto Wilhelm Pfleghard and Max Haefeli designed the building between 1903 and 1906, having become known for their work in Alfred Schellenberg's architectural office.

Since the death of Friedrich Wilhelm Söhnlein in 1938, the villa has had different functions: in 1940 it was rented by the police administration, four years later it was bought by the "Third Reich" and after the end of the war until 1995 it was used by the American military administration.

Places of worship

Old Catholic Church

The parish of the old Catholic Friedenskirche was founded in 1871. While the parishioners were still able to use St. Boniface's Church from 1876, it was finally possible to build their own church in 1898 under the architect Max Schröder. The church, built in the historicizing "pointed arch style" on Schwalbacher Straße, was consecrated in 1900.

Mountain church

When it became clear that the Mauritius Church would become too small for the growing number of worshippers, the construction of a second Protestant church was considered in 1837. However, this plan had to be postponed for the time being, as too many factors intervened: The fire at the Mauritiuskirche, the costly construction of the Marktkirche and the annexation of Nassau in 1866. But as Wiesbaden continued to grow in the founding years, more church space was needed.

The plan by Berlin architect Johannes Otzen won a tender, guaranteeing a construction sum of just 150,000 marks - which was less than a quarter of the cost of building the market church. In the end, however, the sum for the construction amounted to 256,000 marks. Construction began in July 1876, and on May 28, 1879, Bishop Ludwig Wilhelm Wilhelmi consecrated the church "am Berg", which is made of reddish brick and grey Palatinate sandstone.

The residential area around the church grew so close to the church that it eventually took on the name of the church.

St. Boniface Church

In 1831, shortly before the consecration of the new church designed by Friedrich Ludwig Schrumpf, the new building collapsed. The second attempt followed in May 1843: Philipp Hoffmann was commissioned to build the church on Luisenplatz. There had not been a Catholic parish since the Reformation. As the necessary funds for the church building were not available, Pastor Petmecky collected money.

For this reason, the foundation stone was only laid on June 5, 1845, the day of St. Boniface. Bishop Josef Peter Blum of Limburg consecrated the unfinished church in June 1849. Donations had to be collected again for the missing interior fittings and towers that had not yet been built; this work was carried out in the years 1864-66.

After the Mauritius Church burned down in 1850, the Protestant congregation was allowed to use the Catholic Bonifatius Church. However, during the church war of 1876-78, the Catholic community had to hand over their church to the Old Catholic community.

In 1945, the church building was hit by bombs and lost its stained glass.

English church

From 1836, an increasing number of English spa guests stayed in Wiesbaden. As more and more English families moved to the city, they jointly planned the construction of their own church, which was realized in 1863. In addition to their assets, Duke Adolph and the city of Wiesbaden gave the English community the land and a donation of 3,000 guilders.

Senior architect Theodor Goetz built the church at Frankfurter Straße 3 in simple brick Gothic style, following the example of the English "chapels".

Luther Church

With the simple façade of the Lutherkirche, the city's historicism in Protestant church building has almost been overcome in comparison to the other Protestant places of worship such as the Marktkirche, Bergkirche and Ringkirche. Professor Friedrich Pützer built the church at Sartoriusstrasse 16, but considered it inappropriate to use historical forms for new buildings.

The Lutherkirche in Mosbacher Straße was consecrated at Christmas 1910.

The roof of the Lutherkirche is characteristic: at 20 meters high, it takes up more than half the height of the building. The hall can accommodate 1,400 visitors and the Romanesque-influenced Art Nouveau style is particularly evident in the furnishings and colorful decoration on the ceilings and walls. With its large unified space, the Lutherkirche is one of Wiesbaden's churches with the best acoustics.

Maria Hilf Church

The construction of the Catholic Maria-Hilf Church at Kellerstraße 37 goes back to the diocesan master builder Max Meckel, who modeled the church in Kellerstraße on the Romanesque style. With its light sandstone, protruding transept and twin towers, it forms a contrast to the red buildings in the city center.

Market church

The five-towered Marktkirche next to the New Town Hall is the successor to the Mauritiuskirche, which was destroyed by fire in 1850. Its outer walls were no longer considered load-bearing and were therefore unusable for a new interior. Due to a lack of space, the Marktkirche was not built on the former site of the Mauritiuskirche, but on the Neuer Markt. Designed by Carl Boos as the Nassau State Cathedral, the oldest church in the city center is still Wiesbaden's main church today.

It is designed in the Gothic pointed arch style according to the aesthetic ideas of classicism using the clay stone technique. The balanced west façade corresponds most closely to the classicist sensibilities, while the Gothic forms are particularly evident in the towers. The Wiesbaden ceramics workshop Jacob Höppli produced the decorative elements of the Marktkirche in series.

Ring church

According to the plans of architect Johannes Otzen and in consultation with Dean Emil Veesenmeyer, construction of the Ringkirche on Rheinstraße began in 1893. Although its grounds dated back to the beginning of the century, they had since become a bridle path and a tree-lined promenade. As the church was primarily intended to be a meeting place for the congregation with an altar, pulpit and organ in the center, the church was planned as a central building.

Its construction as the third Protestant church after the Marktkirche and the Bergkirche had become necessary due to the rapidly growing number of Protestants in Wiesbaden. With its double-tower façade, the Ringkirche dominates both Rheinstraße and Kaiser-Friedrich-Ring. The Ringkirche was consecrated on Reformation Day in 1894. Accordingly, it was initially known as the "Reformation Church" before its location on the "Ring" earned it the final name Ringkirche.

Russian church

The only Russian Orthodox church in Wiesbaden is located on the Neroberg and is popularly known as the "Greek Chapel". Duke Adolph von Nassau had the burial church built in 1849-1855 for his wife, the Russian Princess Elisabeth Mikhailovna, Grand Duchess of Russia and Duchess of Nassau, who died in childbirth.

The Nassau master builder Philipp Hoffmann erected the church in the style of romantic historicism, following the example of the Church of the Savior in Moscow.

Today, the Russian Orthodox church serves as a parish church for Wiesbaden's Russian community. Adjacent to the building is the Russian cemetery with interesting graves from the 19th century.

Hotels

Hotel Nassauer Hof

Architect Alfred Schnellenberg designed the "Nassauer Hof" hotel in the late historicist style. Built between 1898 and 1907, the new building extended as far as Taunusstraße and replaced the original hotel of the same name built by Zais on the same site. In 1945, the corner building on Taunusstraße was destroyed and a new building was erected in its place in the 1980s. When the Nassauer Hof was rebuilt after the Second World War, two more, rather sober floors were added to the front building on Wilhelmstrasse and the building was finished off with a flat roof.

These alterations diminished the former splendid appearance of the building. On the south wing, however, the neo-baroque building is still recognizable despite the additions. The interior also suffered from the effects of the war, but the atmosphere of the time can still be felt in the large modern rooms.

Hotel Schwarzer Bock

First mentioned in a document in 1486, the "Schwarzer Bock" hotel still closes off Kranzplatz on its south-eastern side and is one of the oldest spa hotels in the city. The hotel's name goes back to the first owner, Mayor Philipp zu Bock, who earned the nickname "Schwarzer Bock" because of his black hair. The building took on its current appearance in 1871/72. The hotel was extended in 1902/03 when the former bathhouse "Zur Goldenen Kette" was added. In the 1960s, the historic charm of the building disappeared with the neoclassical façade and two additional storeys.

Hotel Rose

On the east side of Kochbrunnenplatz is the "Hotel Rose", whose name dates back to 1523, when the then tenant Margarethe zur Rose was sued for rent arrears. In 1896, the owner was finally granted permission to demolish the old building. In its heyday, the hotel with 200 rooms, a large bathing facility and an indoor tennis court welcomed numerous prominent guests.

During the Second World War, the hotel served as a conference venue for the Franco-German Armistice Commission, and from 1945-1948 it was used by the US Air Force. The last owner, Rosenow, reopened the hotel in 1959 after extensive renovations, but reduced the number of beds and rented out the remaining rooms as apartments to permanent guests.

Real estate agent Dr. Jürgen Schneider later planned to turn it into a luxury hotel, but went bankrupt in 1994. Between 2001 and 2004, the state of Hesse converted the building into the state chancellery of the Hessian Minister President.

Former Hotel Oranien

The Wiesbaden architects Schellenberg & Jacobi built the villa on Bierstadt Straße in 1891/92 as the "Hotel Oranien" (a hotel until 1937). From 1928 to 1933, the conductor Carl Schuricht lived in the house, which was built in the late classicist style with baroque elements. After the Second World War, the building became the seat of the Hessian State Chancellery: the Hessian Minister President resided here until 2004. Since the beginning of 2007, it has served as the Hessian Chamber of Architects and Town Planners.

Hotel Bellevue

Art Nouveau and neo-baroque come together in the former Hotel Bellevue in Wilhelmstraße. The façade still looks as it once did; only the stores on the first floor have affected the appearance of the building. Inside, the staircase in particular retains its original features. A large part of the former dining room, now known as the "Bellevue Hall", has also been preserved. An art association for contemporary art called "Verein zur Förderung künstlerischer Projekte mit gesellschaftlicher Relevanz e.V." (Association for the Promotion of Artistic Projects with Social Relevance) holds exhibitions there.

Hotel Grüner Wald

The house with the sandstone façade at Marktstraße 10 is in the neo-baroque style. A stately inn called "Grüner Wald" had stood on the same site since the 16th century. In 1899/1900, the architect Wilhelm Rehbold rebuilt the building as the "Grüner Wald" hotel. Even today, the regular layout of the equally sized balconies bears witness to the building's former function as a hotel. The building was renovated between 1995 and 1997 and has since been used as a residential and commercial building.

Hotel Pariser Hof

The bathhouse "Zum Rebhuhn" or "Rebhinkel" was located in the previous building of the Pariser Hof and was rebuilt after the Thirty Years' War. It had been reserved for Jewish bathers since 1724, and in 1791 the official requirement was added to accommodate a certain number of destitute Jews who were excluded from using the community baths.

Wiesbaden's first rabbi, Abraham Salomon Tendlau, sold the building to Isaak Hiffelsheimer in 1832. The latter acquired the neighboring property and had a larger new building, the "Pariser Hof", built. The Jewish tradition of the house ended with its sale to Friedrich von Wagner.

Over the years, the owners changed, as did the appearance of the building: rococo motifs were placed above the windows on the second floor, which became a characteristic feature of the house. Other features include the arched sandstone windows on the first floor and the entrance door.

The historic "Pariser Hof" bathhouse now houses the "Theater im Pariser Hof" (formerly the "Pariser Hoftheater") and the "Aktive Museum Spiegelgasse".

Hotel "Kurhaus Bad Nerotal"

The listed building at Nerotal 18, together with its predecessor, looks back on around 160 years of history: the merchant Samuel Löwenherz set up a cold-water spa there in 1851 after having his Tuchwalkmühle mill converted. In 1905, the two-and-a-half-storey building was demolished in favor of a taller new building in a simplified Wilhelmine-Neo-Baroque style by the architect Albert Wolff. The "Kurhaus Bad Nerotal" hotel was reopened in April 1907 and enjoyed its most successful years from 1930 onwards, attracting wealthy patients from Germany and abroad. Bombs destroyed the upper floor in 1944 - the two doctors later continued to run the clinic in the intact part of the building until 1957.

In 1992, the Gemeinnützige Wohnungsgesellschaft der Stadt Wiesbaden acquired the villa and began renovation work. Since 1997, the former "Kurhaus Bad Nerotal" has also served as a venue for the private theater "thalhaus".

The former palace hotel was built between 1903 and 1905 to replace two old bathhouses.

During excavation work, the remains of a Roman thermal bath complex were discovered in the excavation pit, proving that people bathed in hot water here in Roman times.

The building quickly became one of Wiesbaden's major hotels, which accommodated numerous famous personalities during its heyday.

Following a conversion in 1976/77, it is still used today as "social housing", certainly one of the most unusual conversions of a grand hotel.

Palace Hotel

Hotel Metropole

The building, which today houses the "Konditorei Kunder" and until 2025 "Teppich Michel", is part of the late historicist construction phase in Wilhelmstrasse. The building was constructed around 1900 as Café Hohenzollern with neo-baroque facades and cupolas. A short time later, the Beckel brothers acquired the building and integrated it into the adjoining "Metropole" hotel. The large dome still dominates Wilhelmstrasse today and plays a key role in shaping the avenue's magnificent appearance.

Public buildings

Government and administration

Town hall

The new town hall was built in the old town between 1883 and 1887. At the time, there were nine buildings on the "island" between Marktstraße and Marktkirche, including the "Koppensteinsche Hof". It was bought by the town in 1868 from senior forester Dr. Dern to house the town hall. The remaining eight houses were demolished.

Known for his town hall building in Munich, the architect Professor Dr. Georg Ritter von Hauberisser was commissioned to design the new town hall, which he implemented in the German Renaissance style.

During the Second World War, the ornate main façade was largely destroyed and only rebuilt in a simplified form. In the course of the reconstruction, historical parts such as the vaulted entrance hall, the staircase and the wide corridor on the second floor were retained.

Hessian Ministry of Culture

The most striking building on Luisenplatz is the "Alte Münze", the former ducal mint. Architect Johann Eberhard Philipp Wolf built it in 1829-30 together with the Pädagogium opposite. Because the emphasis is on the clear cubic and elongated building with its simple structure, the "Alte Münze" represents a special example of the High Classicism period in Wiesbaden.

Hessian Ministry of Science and Art

The former main post office - now the Hessian Ministry of Science and Art - was built in 1904/1905 in the style of a neo-baroque palace building.

The building has a five-axis, three-storey central wing and two tower-like corner pavilions with four storeys, which are closed off by mansard roofs.

Ministry of Justice

In 1834, the decision was made to build a new government building for the Duchy of Nassau. Carl Boos built the administration building between 1838 and 1843. Only a few years later, in 1854, the entire building fell victim to a fire, but was rebuilt in the same year. The architect Philipp Hoffmann was responsible for the renovation and redecoration. In 1925/26, the building was extended: the front on Bahnhofstrasse was lengthened with the addition of an administration building. These façades and two wings parallel to the Luisenstraße / Bahnhofstraße frontage together formed a rectangle whose inner courtyard consisted of the former open garden, the Herrenhof. In 1866, there was a change from the ducal Nassau government to the Prussian administration through the government presidents. A second major upheaval took place in the course of the political upheavals in 1918, when French troops moved into Wiesbaden as an occupying force. The government building survived the Second World War unscathed.

Chamber of Industry and Commerce

The former Erbprinzenpalais is considered the most impressive example of high classicism and is the only surviving large-scale building by architect Christian Zais. The palace was built for Hereditary Prince Wilhelm between 1813 and 1820. However, he never moved into the building because he ascended the ducal throne early.

It was only after Zais' death that the shell of the building was extended in a simple form based on Greek architecture and used as a state library, museum and seat of various authorities. Since 1971, the building has housed the Chamber of Industry and Commerce.

State House

Between 1903 and 1907, the architects Friedrich Werz and Paul Huber built the Landeshaus, which was modeled on the neo-baroque palace building, for the Nassau Provincial Association of Municipalities. The Art Nouveau style was out of the question, as it was a public building commissioned by the Prussian state.

In order to express the representative character, the architects chose red Main sandstone and planned colossal columns that extended through all floors in the central risalit.

The planners enhanced this expression with the wide gable triangle and the mansard roof. The architects Bangert, Jensen, Scholz and Schultes from Berlin were responsible for the extension to the building in 1990/1991, for which they used similar building materials.

Schenck's house

The so-called "Schenck'sche" house - like the Erbprinzenpalais (now the Chamber of Industry and Commerce) - represents the construction phase of classicism in Wiesbaden. In the literature, a connection is often made with Christian Zais, the city's great architect. However, this cannot be scientifically proven. Construction began in 1813, and in 1816 it came into the possession of the Privy Councillor Carl Friedrich Schenck, to whom it owes its name to this day. Wiesbaden only has a few buildings from these early years of the Duchy of Nassau.

It is a stately, impressive building with strikingly harmonious proportions.

Nassau Savings Bank

Duke Adolf founded the Nassauische Landesbank in 1840 when he wanted to transform his duchy into a modern state.

In 1861/62, Richard Görz built the east wing on Rheinstraße, which is still the headquarters of the Nassauische Sparkasse today. Under the arched windows of the original Naspa building are rectangular fields with foliage rosettes as decoration; decorative shapes also adorn the half-pillars. Carl Moritz added an extension in 1914-16; a further harmonious addition was made in the 1960s.

Culture and art

Casino building

Between 1872 and 1874, the architect Wilhelm Bogler built the casino building on behalf of the Wiesbaden Casino Society. The building, which is now a listed building, has a three-storey façade and a special artistic interior design, making it an important representative building in Wiesbaden.

Used as a ballroom, the Herzog-Friedrich-August-Saal, together with the staircase, the foyer, the Hall of Mirrors and the other rooms, makes the casino building an impressive historical event center.

Tattersall

The Tattersall in the Bergkirchen district is named after the English stable master and entrepreneur Richard Tattersall and is synonymous with "riding hall". Albert Wolff built the former riding hall on behalf of riding instructor Ernst Weiß in 1905 based on the English model. 80 horses could be stabled in the stables. The property is located at the rear of the site at Saalgasse 36, with the main façade facing Lehrstraße.

The grandstand inside the building has 500 seats. Today, the Tattersall is used as a community center.

Art house

The Kunsthaus on the Schulberg is built in the style of a palace and was used as an elementary school from 1863 and then as an art school. In 1989, the building was modernized and the studio was refurnished. Since then, the Kunsthaus has provided space for exhibitions and serves as a studio for artists and scholarship holders from all over the world, as well as a workshop for children. The building also houses the offices of the Professional Association of Visual Artists (BBK).

State library

The Hessian State Library building on Rheinstraße was erected in 1913. City building inspector Johannes Grün and city inspector Berlimund were responsible for the planning and construction of the library building. Five lower floors above the basement and main floor serve as stacks. The library was given its current name in 1953 when it was taken over by the state of Hesse; it had previously been known as the "Nassauische Landesbibliothek".

Museum Wiesbaden

Following plans by museum architect Theodor Fischer, work began in 1913 on the three-winged museum building on Friedrich-Ebert-Allee on the site of the former Hessian Ludwigsbahn. The Erbprinzenpalais was extended in 1821 to house the collections of the "Antiquities Society for the Duchy of Nassau" and the "Association for Nassau Antiquities and Historical Research".

The current collection of the Landesmuseum can be traced back to these two societies.

At the end of the 19th century, space in the Erbprinzenpalais became too limited, which led to the planning of a new building. The floor plan of the neoclassical building is based on the division into three collection areas: Nassau Antiquities, Natural History Collections and the Picture Gallery. During his stays at the spa in 1814 and 1815, Goethe urged the construction of a museum, which is why the Goethe monument was placed in the portico of the museum in 1919.

Hessian State Theater

The New Theatre, commissioned and financed by Emperor Wilhelm II, was built between 1892 and 1894 and was officially opened on October 16, 1894 in the presence of the Emperor. The Viennese architects Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer designed the building in the neo-baroque style. The new building replaced the old court theater and the old "Nassauer Hof" spa hotel.

The towering corner dome of the theater became an eye-catcher. City architect Felix Genzmer added the magnificent foyer to the east side of the theater at the emperor's request in 1902. A stage fire in March 1923 destroyed the dome of the stage tower, which could only be rebuilt in a simple form for cost reasons. The formerly richly decorated box office hall and the columned portico fell victim to bombing during the Second World War. Between 1975 and 1978, the auditorium of the Great House was faithfully reconstructed.

Wartburg Castle

The building in Schwalbacher Straße with its sandstone façade bears the name "Wartburg" because it was built for the Wiesbaden Men's Choral Society.

In 1906, the architects Lücke and Euler & Bergen erected the building in the Art Nouveau style.

Today, the Wartburg is a venue of the Hessisches Staatstheater Wiesbaden.

artist house43

The "kuenstlerhaus43" on the edge of the Bergkirchen district is an old Wiesbaden workers' house from the 19th century. In its unrenovated state, it exudes a special charm that takes guests back to times long past and which the artists use specifically for their productions.

Valhalla

Anyone standing in Hochstättenstraße today will hardly be able to imagine that a variety theater from the imperial era is hidden behind the walls. The building was already described by contemporaries as a "magnificent building".

In 2007, the "Walhalla" celebrated its 110th anniversary.

The building has since been acquired by the city of Wiesbaden and is to contribute to the revaluation of the old town area in the future.

Cure

Kaiser-Friedrich-Bad

Thanks to its hot springs, Wiesbaden developed into a world-class spa town. Even the Romans used the "Aquae Mattiacorum" for healing and relaxation according to the motto "Mens sana in corpore sano".

Between 1910 and 1913, the Kaiser-Friedrich-Bad was built as a municipal bathing and spa center in the Art Nouveau style. During the construction of the Kaiser-Friedrichs-Bad, a stone substructure of a Roman sweat bath was uncovered, confirming that the hot Eagle Spring had already been used by the Romans for bathing purposes.

Today's "Kaiser-Friedrich-Therme" covers an area of 1,450 square meters and includes a sauna landscape with the historic Roman-Irish bath at its center.

Spa colonnade

Baurat Heinrich Jacob Zengerle built the northern fountain colonnade in 1826/27. Its rooms are home to the casino's "small game" and provide space for events. In 1839, Baurat Karl Friedrich Faber added the southern "New Colonnade", which has been called the "Theater Colonnade" since the construction of the New Court Theatre. With the exception of the striking six-columned porch, which emphasizes the theater entrance, the southern colonnade is the mirror image of the northern one. In the east and west of both colonnades, a pavilion completes the row of Doric columns.

Spa house

The construction of the Kurhaus marks the architectural highlight of the town's development into a spa resort. Kaiser Wilhelm II officially opened the Kurhaus in 1907; it celebrated its 100th anniversary on May 11, 2007. Kaiser Wilhelm II commissioned the construction of the Kurhaus, which the architect Friedrich von Thiersch designed as a "complete work of Wilhelmine architecture and conception of life". One of the halls was named after him.

The entrance area of the Kurhaus consists of a magnificent lobby with a 21 meter high dome.

Today, the historic Kurhaus, equipped with state-of-the-art technology, is a center for congresses and conferences, exhibitions and cultural events.

Schools

Blücher School

The focal point of the Feldherrenviertel is Blücherplatz, in the center of which stands the Blücher School. It is one of the most important school buildings designed by Felix Genzmer, who built the Blücher School in 1896/97. He used different materials for the building: gray natural stone for the first floor, red clinker brick for the upper floors and gables, yellow sandstone for the decorations and structures.

The school building is rich in ornamental forms, which were modeled by the Cologne sculptor Degen and executed by the Wiesbaden sculptor Schill. The roof tiles on the north wing are of different colors and still show the original pattern.

After the Second World War, the south wing was re-roofed in a simple form and fitted with a trailing dormer. Genzmer drew inspiration for the architectural forms from the Flemish Renaissance and reworked the elements according to his own ideas. The school building already caused a sensation when it was built and was regarded as an exemplary model.

Gutenberg School

The plans for the construction of the Gutenberg School as an elementary school from 1899 onwards met with some adversity in advance: Because the Dichterviertel was earmarked for housing construction due to the increasing population, the school building was not welcomed - especially as a maximum height of 14 meters was specified for the country houses and the school building was to be 18 meters high. In the end, however, the school was built according to Felix Genzmer's plans in two phases, 1901-03 and 1903-05.

In 1933, the building was redesigned to accommodate a grammar school and secondary school. During the Second World War, the south-west wing was destroyed and rebuilt in a simplified form in 1949. After the humanistic grammar school moved out of the building in 1955, only the science and modern languages grammar school remained.

Leibniz School

Felix Genzmer planned the Leibnizschule on Zietenring and his successor, city building inspector Friedrich Grün, built the school in 1903-1905 as an Oberrealschule, a type of school without Latin classes.

In November 1900, Kaiser Wilhelm II gave this type of school the same status as grammar schools.

The building has three floors and consists of three wings surrounding the schoolyard, which is open to the east. As a brick shell with white plaster, the building has simplified Gothic forms.

Oranienschule

Founded as a secondary school in 1857, the Oranienschule is one of the oldest schools in the city. Master builder Alexander Fach built the school building between 1866 and 1868. Although the end of the Duchy of Nassau had already been two years ago, the building was still designed in the late classicist style of Romantic Historicism. Felix Genzmer extended the building in 1896-98, but this was not visible from the street. During a major attack on Wiesbaden in 1945, parts of the school building were destroyed; the school clock on the main building is still a reminder of this day: the hands stopped 20 minutes before midnight.

Former trade school

The former trade school in Wellritzstraße is built of yellow clinker bricks.

Carl A. Hane and Johannes Lemcke erected the building in several sections between 1890 and 1900 in the simple forms of a Prussian state building.

Today, the magnificent building houses a children's and youth center.

Former public buildings

Municipal hospitals

In 1876 and 1879, the municipal hospitals were built between Kastellstrasse, Obere Schwalbacher Strasse and Platter Strasse.

Architects Gropius & Schmieden from Berlin, who specialized in hospital construction, designed the building. In 1976-84, the new Dr. Horst Schmidt Clinics in Dotzheim replaced the municipal hospitals. The three simple red brick foundation buildings at the junction of Kastellstrasse and Schwalbacher Strasse have been preserved.

Johannesstift

Mathilde Grossmann, Julie Matuschka-Greiffenclau and Anna Schipper founded the "Johannesstift Welfare Association" in 1906, which looked after "fallen girls" and female prisoners. One year later, Mathilde Grossmann donated the building at 78 Platter Strasse to the association, which was consecrated by the Bishop of Limburg and from then on bore the name "Johannesstift". In 1908, the building was extended to include an infant home.

The Second World War caused considerable damage to the building. At the same time, those in power at the time demanded that the Johannesstift be used as an auxiliary hospital. After the end of the war, the Johannesstift was renovated and extended.

Industrial culture

Central station

On November 13, 1906, the main station was inaugurated as a central building of late historicism. It replaced the three previous stations Taunusbahnhof, Rheinbahnhof and Ludwigsbahnhof. Professor Fritz Klingholz, an architect from Aachen, was responsible for the planning, which was regularly supervised by spa guest Kaiser Wilhelm II. Like the previous stations, the main station was also designed as a terminus station to avoid the noise of passing trains and to accommodate the spa guests, who did not have to negotiate any stairs in the new station. In keeping with the prestige of a cosmopolitan spa town and its guests, red sandstone was chosen as the building material. The 40-metre high clock tower is a characteristic feature of the station. The imperial reception hall was destroyed during the Second World War, but was not rebuilt afterwards.

Henkell sparkling wine cellar

Paul Bonatz built the "Henkellsfeld" in neoclassical style between 1907 and 1909 on behalf of Otto Henkell. The result was a three-storey "palace for sparkling wine" with modern structures. Although Bonatz's design takes up features of baroque palace buildings, it is indebted to Palladio in its idea, intention and execution. The austerity of the three-winged complex with its cour d'honneur is offset by an arcade. This portico also refers to Palladio, but Zais' straight Kurhaus colonnades are also often cited as a model.

The flat side wings with the corner pavilions form a courtyard of honor, which was to be used specifically for advertising purposes.

The plans for the sparkling wine cellar also included the large-format lettering on the roof ridge as advertising, which was part of the architectural competition.

Nerobergbahn

The valley station of the Nerobergbahn is located at the end of the upper Nero valley. In front of it is a half-timbered toilet block designed by Felix Genzmer in 1897/98. Today it houses a museum on the history of the Nerobergbahn. The Nerobergbahn was opened in 1888; its technology has remained unchanged ever since. The railroad, which is operated with water ballast and whose carriages are constructed to suit the gradient, climbs the Neroberg in just a few minutes over a length of 438.5 m, overcoming the even gradient of around 25 percent. Two carriages are connected by a steel cable and meet in the middle of the line, where they can pass each other by means of points. To save drinking water, the approximately 7,000 liters of water are now drained into a collecting basin and transported back up by pumps.

Salzbach Canal

Wiesbaden's canal system was built between 1900 and 1907.

The accessible canals were already considered a tourist attraction in the imperial era: the Wiesbaden Canal Construction Office invited visitors on guided tours and sold a small guide through the underworld of Wilhelmstraße from Warme Damm to Mühltal for ten pfennigs.

The Salzbach canal, consisting of artfully masoned basket arches, seven meters below Wilhelmstraße and Friedrich-Ebert-Allee, is a special feature of the canal network. The channel of the Salzbach, which is 4.5 meters high and five meters wide, is lined with sidewalks. The channel can drain a volume of water of around 85,000 liters per second.

Biebrich water tower

The Biebrich water tower, located not far from Biebricher Allee and Henkellfeld, was built in 1896/97 and offers a wonderful view of Biebrich, Wiesbaden and the Rhine Valley thanks to its height of around 42 meters.

However, you have to climb 238 steps to enjoy the view.

Press House

The site where the Wiesbadener Kurier press building has stood since 1904 was once home to Schellenberg's court printing works.

The architects Lang & Wolff built the press house from red sandstone and chose forms from late historicism as well as individual elements from Art Nouveau. The copper statue "Knowledge" by the sculptor Philipp Modrow stands on the roof ridge.

The Art Nouveau style is particularly evident in the painterly design of the interior and in the stained glass windows.

House Höppli

The building in Wiesbaden's Wörthstraße was built by the Swiss Jacob Höppli to house his "Thonwaaren und Fayencen-Fabrik" (clay ware and faience factory).

It was used for the production of architectural ceramics, which were used for the design of numerous villas in Wiesbaden.

Built between 1872 and 1876 in the style of the Italian Renaissance, the house is characterized by the "caryatids", four female sculptures that support the decorative entablature. The building was planned by the Wiesbaden architect Georg Friedrich Fürstchen.

Höppli died in 1876 at the age of 54. Höppli's descendants continued to run the artistic workshop until 1910 and descendants of the "Thonwaarenfabrikanten" lived in the Höppli House until 1992.

Cemeteries

Old cemetery

Since its inauguration in 1832, the so-called "Old Cemetery" on Platter Straße was considered a site with an almost "picturesque charm", where "Old Nassau" and its personalities were buried. The tourist guide from 1873 noted: "The cemetery, adorned by its magnificent location and beautiful plantings, as well as its beautiful monuments by local and foreign sculptors, is one of the most beautiful cemeteries in Germany".

In 1877, the decision was made to build a new cemetery, the North Cemetery. The now "old" cemetery was only used for burials in family graves. Nevertheless, the last burial, an urn burial in a crypt, did not take place until 1955.

In the 1970s, the site was transformed into a leisure and recreation park: 128 burial monuments worthy of preservation were recorded and, if necessary, moved. In the center of the grounds, which were inaugurated in 1977, there are now several children's playgrounds and barbecue facilities.

North cemetery

As the second largest cemetery in Wiesbaden, the North Cemetery, opened in 1877, covers an area of 145,000 square meters.

The former Platter Straße 13 cemetery is the predecessor of the North Cemetery, which was laid out on the ridge between Nerostal and Adamstal.

Numerous important personalities found their final resting place here. Due to its old and valuable tree population, which dates back to the time of its establishment, the cemetery today is characterized by its woodland character - predominantly characterized by trees of life and cypresses. The grounds contain many graves from the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Due to the large number of artistically significant gravestones and the architectural and landscaping design, the cemetery on Platter Straße is now a listed building.

South cemetery

The southern cemetery, laid out in the style of baroque garden ideals and designed by horticultural inspector Heinrich Zeininger, was created in 1908/1909 as the second main municipal cemetery after the northern cemetery.

The central structure of the symmetrical building arrangement is the crematorium, which was one of the first cremation facilities in Prussia to go into operation in 1912. Covering an area of 330,700 square meters, the South Cemetery contains numerous historic gravesites, some of the most representative of which are located along the Ringweg.

Russian cemetery

In 1856, one year after the consecration of the Russian Church, Grand Duchess Jelena, the mother of the late Duchess Elisabeth, had the idea of establishing a cemetery where people of the Russian Orthodox faith could find their final resting place. Philipp Hoffmann, builder of the chapel, was commissioned to design the cemetery, which was to harmonize with the Duchess's burial church.

Hoffmann planned the cemetery in the form of a cross with rounded corners and a brick wall enclosure; a gilded Russian cross adorned the entrance gate. The cemetery was consecrated in August of the same year. In 1864, the cemetery passed from ducal-Nassau ownership to that of the Russian Church.

City archive

Address

65197 Wiesbaden

Postal address

65029 Wiesbaden

Arrival

Notes on public transport

Public transportation: Bus stop Kleinfeldchen/Stadtarchiv, bus lines 4, 17, 23, 24 and 27 and bus stop Künstlerviertel/Stadtarchiv, bus line 18.

Telephone

- +49 611 313022

- +49 611 313977

Opening hours

Opening hours of the reading room:

- Monday: 9 a.m. to 12 p.m.

- Tuesday: 9 am to 4 pm

- Wednesday: 9 am to 6 pm

- Thursday: 12 to 16 o'clock

- Friday: closed